Could the apparent increased stroke risk in vegetarians be reverse causation? And what about vegetarians versus vegans?

In the “Risks of Ischaemic Heart Disease and Stroke in Meat Eaters, Fish Eaters, and Vegetarians Over 18 Years of Follow-Up” EPIC-Oxford study, not surprisingly, vegetarian diets were associated with less heart disease—10 fewer cases per 1,000 people per decade compared to meat eaters—but vegetarian diets were associated with three more cases of stroke. So, eating vegetarian appears to lower the risk of cardiovascular disease by 7 overall, but why the extra stroke risk? Could it just be reverse causation?

When studies have shown higher mortality among those who quit smoking compared to people who continue to smoke, for example, we suspect “reverse causality.” When we see a link between quitting smoking and dying, instead of quitting smoking leading to people dying, it’s more likely that being “affected by some life-threatening condition” led people to quit smoking. It’s the same reason why non-drinkers can appear to have more liver cirrhosis; their failing liver led them to stop drinking. This is the “sick-quitter effect,” and you can see it when people quit meat, too.

As you can see below and at 1:16 in my video Vegetarians and Stroke Risk Factors: Vitamin D?

, new vegetarians can appear to have more heart disease than non-vegetarians. Why might an older person all of a sudden start eating vegetarian? Well, they may have just been diagnosed with heart disease, so that may be why there appear to be higher rates for new vegetarians—an example of the sick-quitter effect. To control for that, you can throw out the first five years of data to make sure the diet has a chance to start working. And, indeed, when you do that, the true effect is clear: a significant drop in heart disease risk.

So, does that explain the apparent increased stroke risk, too? No, because researchers still found higher stroke risk even after the first five years of data were skipped. What’s going on? Let’s dive deeper into the data to look for clues.

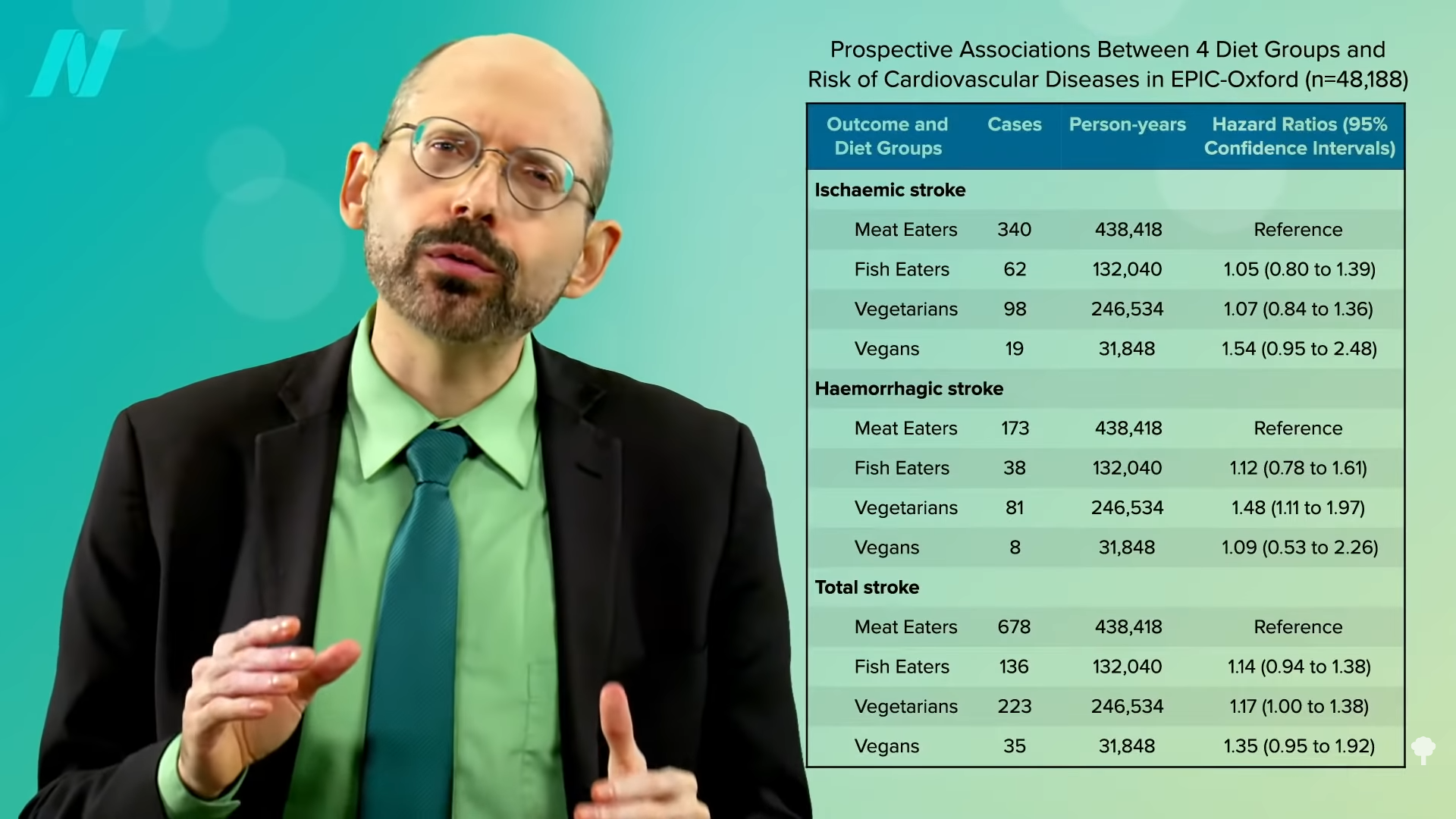

What happens when you break down the results by type of stroke and type of vegetarian (vegetarian versus vegan)? As you can see below and at 2:09 in my video, there are two main types of strokes—ischemic and hemorrhagic. Most common are ischemic, clotting strokes where an artery in the brain gets clogged off, as opposed to hemorrhagic, or bleeding strokes, where a blood vessel in the brain ruptures. In the United States, for example, it is about 90:10, with nine out of ten strokes the clotting (ischemic) type and one out of ten bleeding (hemorrhagic), the latter being the kind of stroke vegetarians appeared to have significantly more of. Now, statistically, the vegans didn’t have a significantly higher risk of any kind of stroke, but that’s terrible news for vegans. Do vegans have the same stroke risk as meat eaters? What is elevating their stroke risk so much that it’s offsetting all their natural advantages? The same could be said for vegetarians, too.

Even though this was the first study of vegetarian stroke incidence, there have been about half a dozen studies on stroke mortality. The various meta-analyses have consistently found significantly lower heart disease risk for vegetarians, but the lower stroke mortality was not statistically significant. Now, there is a new study that can give vegetarians some comfort in the fact that they at least don’t have a higher risk of dying from stroke, but that’s terrible news for vegetarians. Statistically, vegetarians have the same stroke death rate as meat eaters. Again, what’s going on? What is elevating their stroke risk so much that it’s offsetting all their natural advantages?

Let’s run through a couple of possibilities. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:48 in my video, if you look at the vitamin D levels of vegetarians and vegans, they tend to run consistently lower than meat eaters, and lower vitamin D status is associated with an increased risk of stroke. But who has higher levels of the sunshine vitamin? Those who are running around outside and exercising, so maybe that’s why their stroke risk is better. What we need are randomized studies.

When you look at people who have been effectively randomized at birth to genetically have lifelong, lower vitamin D levels, you do not see a clear indicator of increased stroke risk, so the link between vitamin D and stroke is probably not cause-and-effect.

We’ll explore some other possibilities, next.

So far in this series, we’ve looked at what to eat and what not to eat for stroke prevention, and whether vegetarians do have a higher stroke risk.

It may be worth reiterating that vegetarians do not have a higher risk of dying from a stroke, but they do appear to be at higher risk of having a stroke. How is that possible? Meat is a risk factor for stroke, so how could cutting out meat lead to more strokes? There must be something about eating plant-based that so increases stroke risk that it counterbalances the meat-free benefit. Might it be because plant-based eaters don’t eat fish? We turn to omega-3s next. For other videos in this series, see related posts below.

There certainly are benefits to vitamin D, though. Here is a sampling of videos where I explore the evidence.