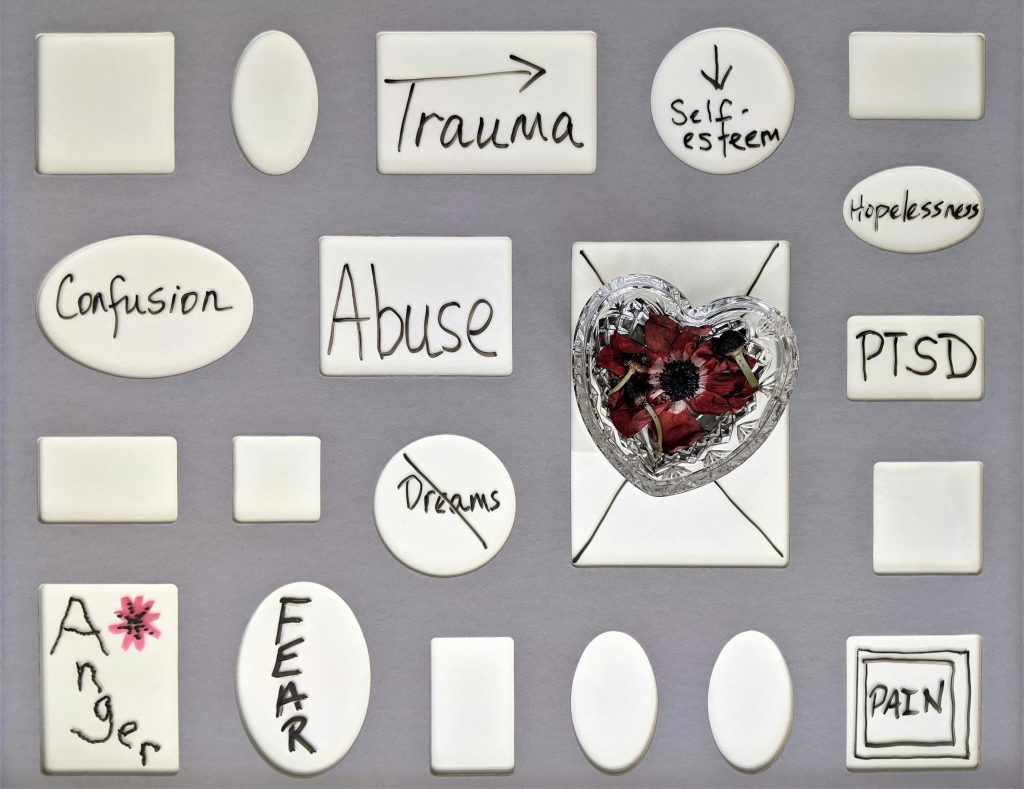

The concept of Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) in healthcare has emerged due to the recognition of the profound impact of traumatic experiences on mental health (Edwards et al., 2003). Trauma lacks a universal definition, but the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes it as events perceived as harmful or life-threatening with long-lasting adverse effects on well-being (Huang et al., 2014). High levels of trauma are reported among individuals using mental health services, with significant prevalence among those in acute settings and with severe mental health conditions. Staff in these environments also face work-related trauma, leading to reciprocal traumatisation (Rössler, 2012).

Overall, TIC aims to understand the links between trauma and mental health, providing comprehensive responses to avoid re-traumatisation. TIC involves recognising the links between trauma and mental health, acknowledging social trauma and multiple intersecting traumas, conducting sensitive inquiries into trauma experiences, and referring individuals to evidence-based trauma-specific support (Sweeney & Taggart, 2018). It also addresses vicarious trauma, emphasises trust and transparency, fosters collaborative relationships with service users, adopts a strengths-based approach, and prioritises the emotional and physical safety of service users. This previous blog by Zarska (The Mental Elf, January, 2022) describes a bit more why we need TIC and what it should look like in the mental health settings. Other information sources, including previous research, suggest that TIC’s principles must be embedded in policy and practice, which can be challenging in acute settings (Bryson et al, 2017).

In their recent scoping review around TIC, Kitty Saunders and colleagues (2023) aimed to identify and explore TIC approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care, focusing on service user and staff experiences, outcomes, practices, well-being, and cost-effectiveness. The review seeks to map these approaches, highlighting gaps and variability in the literature and service provision.

Trauma Informed Care has many definitions, which makes it difficult to evaluate the effectiveness of such services.

Methods

A scoping review was used to explore and summarise a wide array of studies on TIC. The authors included studies focusing on trauma-informed care (TIC) in various mental health settings, including acute, crisis, emergency, and residential care. They also incorporated a broad range of study types, such as qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-method research, as well as service descriptions, evaluations, and case studies. The authors searched multiple databases, grey literature sources, and contacted experts to ensure a broad range of studies were considered.

The review combined data narratively rather than quantitatively, which was reasonable given the diversity of study designs and data types. Narrative synthesis allowed for the integration of both qualitative and quantitative data, highlighting common themes and variations in TIC approaches.

Results

The search identified 31 studies that met the inclusion criteria. The most common Trauma Informed Care (TIC) models were the Six Core Strategies (7 studies) and the Sanctuary Model (6 studies). Most studies were from the USA (23), with others from the UK (5), Australia (2), and Japan (1). They mainly focused on acute services (16 studies) and residential treatment (14 studies), with one in an NHS crisis house. Over a third were in child and adolescent settings (12), and six were in women’s services.

Six Core Strategies

- Implemented primarily to reduce seclusion and restraint, based on trauma-informed and strengths-based care.

- Studies show reductions in restraint and seclusion practices, improved staff attitudes, empathy, and team cohesion.

- Service users were more involved in their care, leading to better outcomes and reduced hospital admissions.

Sanctuary Model

- Applied in child and adolescent residential settings to promote safety and recovery.

- Studies reported decreased absconsion, restraint, and removal from programs, improved staff attitudes, and a healthier organisational culture.

- Staff focused on recovery and adapted empathetic approaches towards service users.

Comprehensive tailored trauma-informed models

- Developed to meet specific needs of various settings, including child and adolescent residential treatments and adult women-only substance misuse services.

- Key features include staff training, therapeutic environments, family-cantered approaches, and collaborative agency work.

- Positive outcomes included reduced seclusion and restraint, improved staff empathy, and service user engagement.

Safety-focused tailored trauma-informed models

- Aimed to create a culture of safety and reduce restrictive practices.

- Studies reported reductions in seclusions and restraints and improved therapeutic relationships.

- Staff developed new tools for trauma response and communication.

Trauma-informed training interventions

- Focused on equipping staff with knowledge and skills to implement TIC.

- Training resulted in positive attitude shifts, modified communication, and reduced coercive practices.

Other TIC models

- Involved attempts to shift towards trauma-informed approaches without full-scale implementation.

- Positive outcomes included reduced seclusion rates and improved staff confidence and motivation.

Overall, TIC approaches enhanced service user involvement, reduced restrictive practices, and improved staff wellbeing and organisational culture. However, the implementation was resource-intensive, required ongoing training, and there were challenges related to staff adaptation and sustainability.

Trauma informed care in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care settings enhanced service user involvement, reduced restrictive practices and improved staff wellbeing.

Conclusions

This scoping review highlights the diverse Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) approaches in acute, crisis, and residential settings, along with their effects on service users and staff. It seems that successful TIC implementation demands strong leadership, staff training, supervision, and active involvement of service users (Saunders et al., 2023).

According to this scoping review, trauma informed care demands strong leadership, staff training, supervision and the active involvement of service users.

Strengths and limitations

One of the difficulties in reviewing research on Trauma Informed Care (TIC) is the heterogeneity in TIC models. TIC is implemented in various ways across different settings, leading to a wide variety of approaches and definitions. This variability makes it difficult to compare studies or generalise findings across different contexts.

As mentioned by the authors, many of the included studies lack control or comparison groups. Without these, it’s hard to establish causality or the true impact of TIC. The authors further state that there were common methodological weaknesses across the reviewed studies, with many being cross-sectional making it difficult to draw firm causal conclusions about TIC’s impacts.

The review described a thorough data extraction process but did not explicitly mention a formal quality assessment of the included studies. Scoping reviews generally focus on mapping and summarising evidence rather than critically appraising quality. While the review team included rigorous screening and data extraction methods, a more detailed assessment of study quality could strengthen the review’s findings, particularly given the diverse study designs and methodologies included.

It was also noted that much of the TIC research relies on qualitative data, such as interviews and case studies, which are valuable but harder to quantify and compare across studies. This makes it challenging to perform rigorous, objective evaluations of TIC’s effectiveness.

The scoping review by Saunders et al., (2023) included a good number of relevant studies, which helped to increase the reliability and validity of the fundings. TIC is often expected to create long-term changes in service delivery and outcomes, but measuring these long-term impacts can be challenging, especially in the face of high staff turnover or changes in organisational priorities.

This scoping review on TIC focused on existing academic and grey literature, which may lack current survivor perspectives on TIC, particularly regarding potential harms of poor implementation, such as feeling coerced into confronting trauma. The studies reviewed were diverse in their outcome measures, which limited the generalisability of the findings. More data was available on residential mental health settings, possibly due to their suitability for long-term TIC implementation, but this left other settings underrepresented.

Trauma informed care is often expected to create long-term changes in service delivery and outcomes, but measuring these long-term impacts can be challenging, especially in the face of high staff turnover or changes in organisational priorities.

Implications for practice

As most of the research on the topic suggests, the implementation of Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) in inpatient and residential settings requires strong leadership, clear staff roles, and collaboration with service users to ensure safe and appropriate care (Saunders et al., 2023). The authors suggest that TIC should be integrated into pre-registration education for healthcare professionals and included in new staff inductions. Consistent staff supervision is crucial, but sustainability is challenged by the resource-intensive nature of training and high staff turnover rates. Service users should have the choice of whether or not to confront their trauma, and TIC should not be contingent on their willingness to engage with it.

The authors suggest that future research should use robust methods to measure TIC’s impact compared to existing practices and explore its effects on carers, its application in emergency services, and incorporate the perspectives of those with lived experience to optimise TIC delivery.

At the end of their review, Saunders et al., (2023) include a commentary from trauma survivors, helping us to see another angle of this topic. Although they acknowledge some positive outcomes, the survivors question whether a system that involves violence can ever be truly non-traumatising. They caution that TIC, particularly when implemented in under-resourced and punitive environments, may perpetuate harm under the guise of care. They urge those providing TIC to critically examine the power dynamics and consider returning more control to patients over their own experiences and narratives. Read Sarah Carr’s excellent 2018 blog: Trauma-informed approaches in mental health: co-optable and corruptible? to delve more into this topic.

The present study could be also extended to map the use of TIC in forensic settings, where poor mental health and experiences of trauma are also highly prevalent.

Future primary research could explore implementation of TIC in emergency and crisis mental health care settings, where it may be more difficult to implement a consistent and sustainable TIC approach as service users are engaged for shorter time periods. Future research could also consider the potential negative and harmful impacts of TIC.

As a clinician with experience of working in both acute and secondary care services, I believe trauma-informed care is key to providing truly person-centered, holistic support to service users. Understanding trauma’s impact allows us to create trust and safety, tailoring our approach to meet each individual’s needs.. Embracing trauma-informed care means treating everyone with the dignity and understanding they deserve, leading to more compassionate and effective mental health services.

This review suggests that trauma-informed care should be taught to training professionals to ensure adoption in services.

Statement of interests

Magda is a clinician in secondary care services. No conflicts of interest to declare.

Links

Primary paper

Saunders, K.R.K., McGuinness, E., Barnett, P. et al. A scoping review of trauma informed approaches in acute, crisis, emergency, and residential mental health care. BMC Psychiatry 23, 567 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05016-z

Other references

Bowers, L. (2014). Safewards: A new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(6), 499–508. DOI: 10.1111/jpm.12129

Bryson, S. A., Gauvin, E., Jamieson, A., Rathgeber, M., Faulkner-Gibson, L., Bell, S., et al. (2017). What are effective strategies for implementing trauma-informed care in youth inpatient psychiatric and residential treatment settings? A realist systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11(1), 1–16. DOI: 10.1186/s13033-017-0137-3

Edwards, D. W., Scott, C. L., Yarvis, R. M., Paizis, C. L., & Panizzon, M. S. (2003). Impulsiveness, impulsive aggression, personality disorder, and spousal violence. Violence and Victims, 18(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.2003.18.1.3

Huang, L. N., Flatow, R., Biggs, T., Afayee, S., Smith, K., Clark, T., et al. (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. http://hdl.handle.net/10713/18559

Rössler, W. (2012). Stress, burnout, and job dissatisfaction in mental health workers. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 262(2), 65–69. DOI: 10.1007/s00406-012-0353-4

Sweeney, A., Filson, B., Kennedy, A., Collinson, L., & Gillard, S. (2018). A paradigm shift: Relationships in trauma-informed mental health services. BJPsych Advances, 24(5), 319–333. DOI: 10.1192/bja.2018.29

Sweeney, A., & Taggart, D. (2018). (Mis)understanding trauma-informed approaches in mental health. In Trauma-Informed Approaches to Mental Health (pp. 383–387). Taylor & Francis. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1520973

Zarska, A. (2022, January 25th) National Elf Service. The Mental Elf. Trauma-informed mental health care. National Elf Service. https://www.nationalelfservice.net/mental-health/ptsd/trauma-informed-mental-health-care/