SAD doesn’t just stand for the standard American diet.

There’s a condition known as seasonal affective disorder that is characterized by increased appetite and cravings, as well as greater sleepiness and lethargy, that begins in autumn when light exposure starts to dwindle. This now appears to represent the far end of a normal spectrum of human behavior. We appear to eat more as the days get shorter. There is a “marked seasonal rhythm” to calorie intake with greater meal size, eating rate, hunger, and overall calorie intake in the fall.

In preparation for winter, some animals hibernate, doubling their fat stores with autumnal abundance to deal with the subsequent scarcity of winter. Genes have been identified in humans that are similar to hibernation genes, which may help explain why we exhibit some of the same behaviors, and the autumn effect isn’t subtle. As you can see in the graph below and at 1:06 in my video Friday Favorites: Why People Gain Weight in the Fall, researchers calculated a 222-calorie difference between how many calories we consume in the fall versus the spring. This isn’t just because it’s colder, either, since we eat more in the fall than in the winter. It appears we’re just genetically programmed to prep for the deprivation of winter that no longer comes.

It’s remarkable that, in this day and age of modern lighting and heating, our bodies would still pick up enough environmental cues of the changing seasons to have such a major influence on our eating patterns. Unsurprisingly, bright light therapy is used to treat seasonal affective disorder, nearly tripling the likelihood of remission, compared to placebo. Though it’s never been tested directly, it can’t hurt to take the dog out for some extra morning and daytime walks in the fall to try to fend off some of the coming holiday season weight gain.

People blame the holidays for overeating, but it may be that “rather than the holidays causing heightened intake, the seasonal heightening of intake in the fall may have caused the scheduling of holidays at that time.”

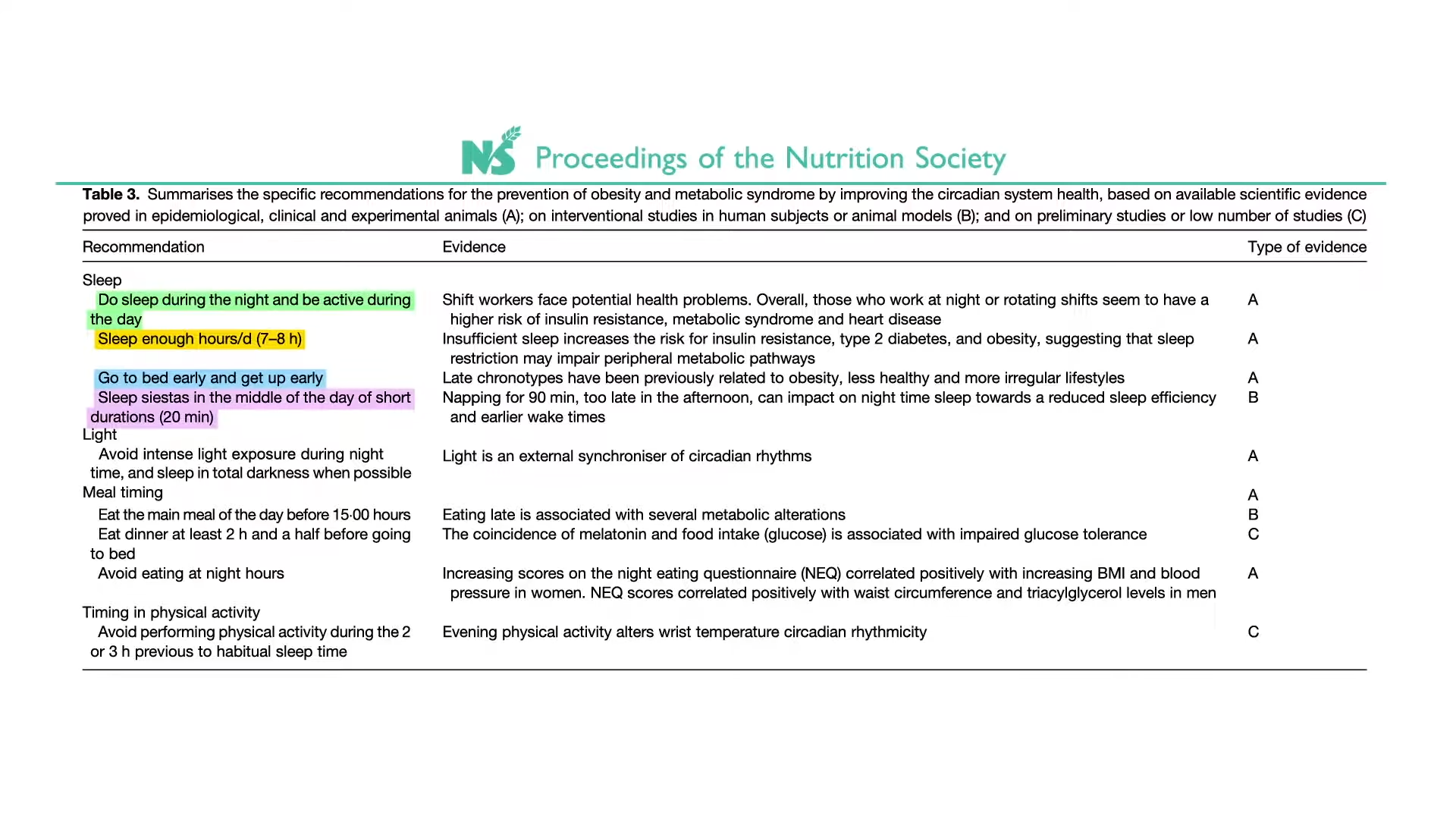

Regardless, as you can see below and at 2:15 in my video, other “specific recommendations for the prevention of obesity and metabolic syndrome by improving the circadian system health,” based on varying degrees of evidence, include: sleeping during the night and being active during the day; sleeping enough—at least seven or eight hours a night; early to bed, early to rise; and short naps are fine. (Contrary to popular belief, daytime napping does not appear to adversely impact sleep at night.) Also recommended: avoiding bright light exposure at night; sleeping in total darkness when possible; making breakfast or lunch your biggest meal of the day; not eating or exercising right before bed; and completely avoiding eating at night.

This was the last video in my chronobiology series. If you missed any of the others, check out the related posts below.

This was the last video in my chronobiology series. If you missed any of the others, check out the related posts below.