The story of the discovery of the planet Neptune is particularly interesting. It started with Alexis Bouvard (1767-1843), a French astronomer who lived at the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth century.

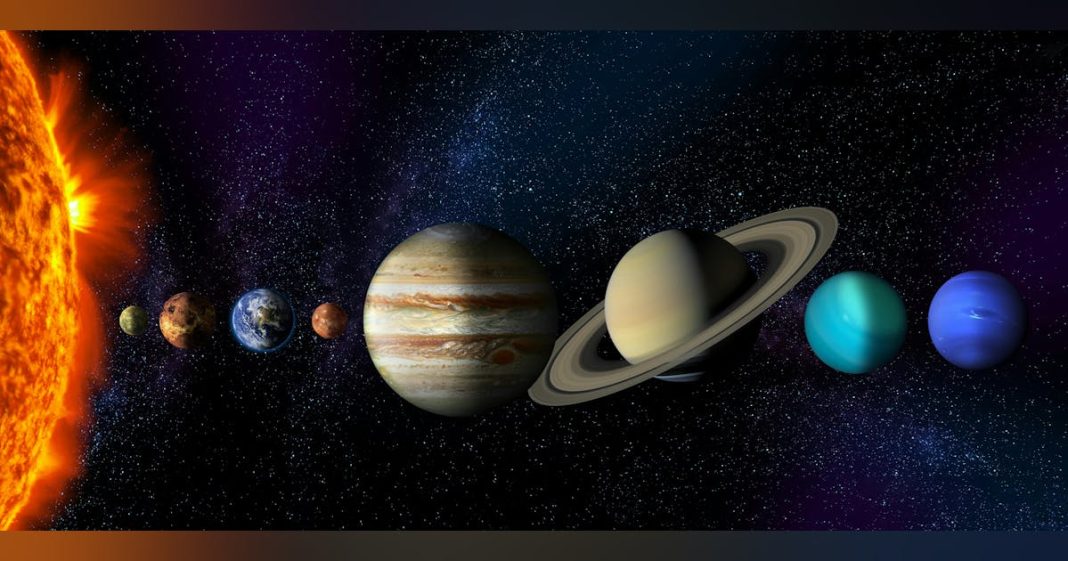

Bouvard, born in the village of Contamines in what was then the Duchy of Savoy and is now the department of Haute Savoie in the Alps of southeastern France, discovered eight comets, and compiled astronomical tables for the planets Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus (whose status as a planet had only been confirmed in 1781 by German-British astronomer William Herschel).

As Wikipedia notes, referring to Jupiter and Saturn, “While the former two tables were eminently successful, the latter showed substantial discrepancies with subsequent observations. This led Bouvard to hypothesise the existence of an eighth planet responsible for the irregularities in Uranus’ orbit. The position of Neptune was subsequently calculated from Bouvard’s observations by Urbain Le Verrier after his death.”

Wikipedia further notes that, “After Bouvard’s death, the position of Neptune was predicted from his observations, independently, by John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier. Neptune was subsequently directly observed with a telescope on 23 September 1846 by Johann Gottfried Galle within a degree of the position predicted by Le Verrier. Its largest moon, Triton, was discovered shortly thereafter, though none of the planet’s remaining 15 known moons were located telescopically until the 20th century. The planet’s distance from Earth gives it a small apparent size, making it challenging to study with Earth-based telescopes. Neptune was visited by Voyager 2, when it flew by the planet on 25 August 1989; Voyager 2 remains the only spacecraft to have visited it. The advent of the Hubble Space Telescope and large ground-based telescopes with adaptive optics has allowed for additional detailed observations from afar.”

All of this is fascinating science, considering that, unlike Jupiter, Saturn, and (very vaguely) Uranus, Neptune is not only the final recognized planet (the status of Pluto was recently reduced to “dwarf planet,” for a number of reasons), but also because of its incredible distance from both the Sun and from Earth. The Earth is 93 million miles from the Sun, but Neptune is another nearly 3 billion miles out in space. It is also massive, at 17 times the size of Earth.

The kinds of scientists who have viewed, calculated, and mapped the Solar System have blazed huge trails for society, and even now, continue to send satellites out to nearly the edge of the Solar System, bringing back a wealth of information to us earthlings.

And of course, one lesson in all this is that things are complicated, and many big questions can’t quickly or easily be resolved. The same could easily be said for this current moment in the U.S. healthcare delivery and payment system, with its enormous layers and complexities. Just a few weeks ago, on June 12, the Medicare Actuaries inside the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), released their annual projections for overall U.S. healthcare system spending, determining that total annual U.S. spending on healthcare is set to leap from the current $4.8trillion as of last year, to a mindblowing $7.7 trillion by 2032, and will suck up fully 19.7 percent of total U.S. GDP (gross domestic product).

As I noted in a blog I posted shortly after the new projections were released, if ever the leaders of the U.S. healthcare system had a burning platform for change, that would be it. Inevitably, the aging of the population and the ongoing explosion in chronic disease rates mean that it will be an uphill battle all the way. For one thing, hospitals, large medical groups, and health systems nationwide are facing ever-growing staffing shortages, most particularly of nurses—but also of IT staff and revenue cycle management professionals, among others. At the same time, the costs of just about everything, including supplies and equipment, continue to go up.

Those issues and more are thoroughly discussed in the latest publication from Healthcare Innovation, our “Executive Handbook: Top Priorities 2024.” In that brand-new publication, we interview industry-leading experts who share their insights around finance and revenue cycle management, the ongoing, complicated shift into value-based contracting, the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence and machine learning, the top issues in cybersecurity, and the work underway to optimize the patient experience.

The good news is that none of the industry experts and patient care organization leaders we spoke to are trying to make anyone believe that the slate of challenges facing the U.S. healthcare system are going to be solved quickly or easily. For one thing, the United States is facing some very fundamental issues common to all the advanced, industrialized nations: a rapidly aging population whose percentage of seniors with medical needs is growing faster than the necessary influx of younger citizens and residents in the workforce whose taxed labor can support the necessary expansion of medical care; and a nonstop increase in labor costs that is global. And our U.S. healthcare system also has, unfortunately, a massive administrative infrastructure that largely does not exist in the other major healthcare systems, and, depending on whom one is talking to, might account for as much as one-fifth of the total costs of the nationwide healthcare system (again, depending on whom is talking to).

None of this is going to be solved anytime son. But the other good news in all this is that the leaders of the most pioneering patient care organizations, as well as future-thinking policy and payment leaders, are working hard to make our healthcare system more cost-effective and operationally efficient and capable of producing better patient outcomes at higher value. It’s all hard work, but the most innovative leaders in U.S. healthcare are determined to help us all get there.

And ultimately, the healthcare system is becoming a learning system over time. Who knows what developments might take place that will be parallel to Alexis Bouvard’s deduction of a mysterious final planet, in the early nineteenth century? There will always be new worlds to discover—and the leaders of our healthcare system are going to be making major discoveries going forward.